Introduction –

PVC processors face a paradoxical reality: even when using identical stabilizer packages, PVC thermal stability outcomes can diverge wildly under different mixer speeds or processing conditions[1][2]. This is more than a laboratory curiosity—it’s a daily PVC processing challenge on the production floor. A formulation that performs flawlessly in one plant might show early yellowing or degradation in another, leaving engineers and technicians puzzled. The root cause often isn’t the stabilizer itself, but how it’s dispersed and processed. In this deep dive, we explore the science behind stabilizer dispersion and practical PVC stabilizer troubleshooting strategies. We’ll highlight why mixer speed, shear rate, and thermal history can make or break stabilizer effectiveness, and provide a real-world troubleshooting checklist (plus a handy flowchart) for polymer engineers. Whether you’re managing a mixing line or optimizing extrusion parameters, these insights will help ensure consistent PVC thermal stability. (And as we gear up for Orbimind’s upcoming Future of PVC Conference, we’ll connect these lessons to the broader industry conversation.)

🔍 The Science Behind Stabilizer Dispersion in PVC

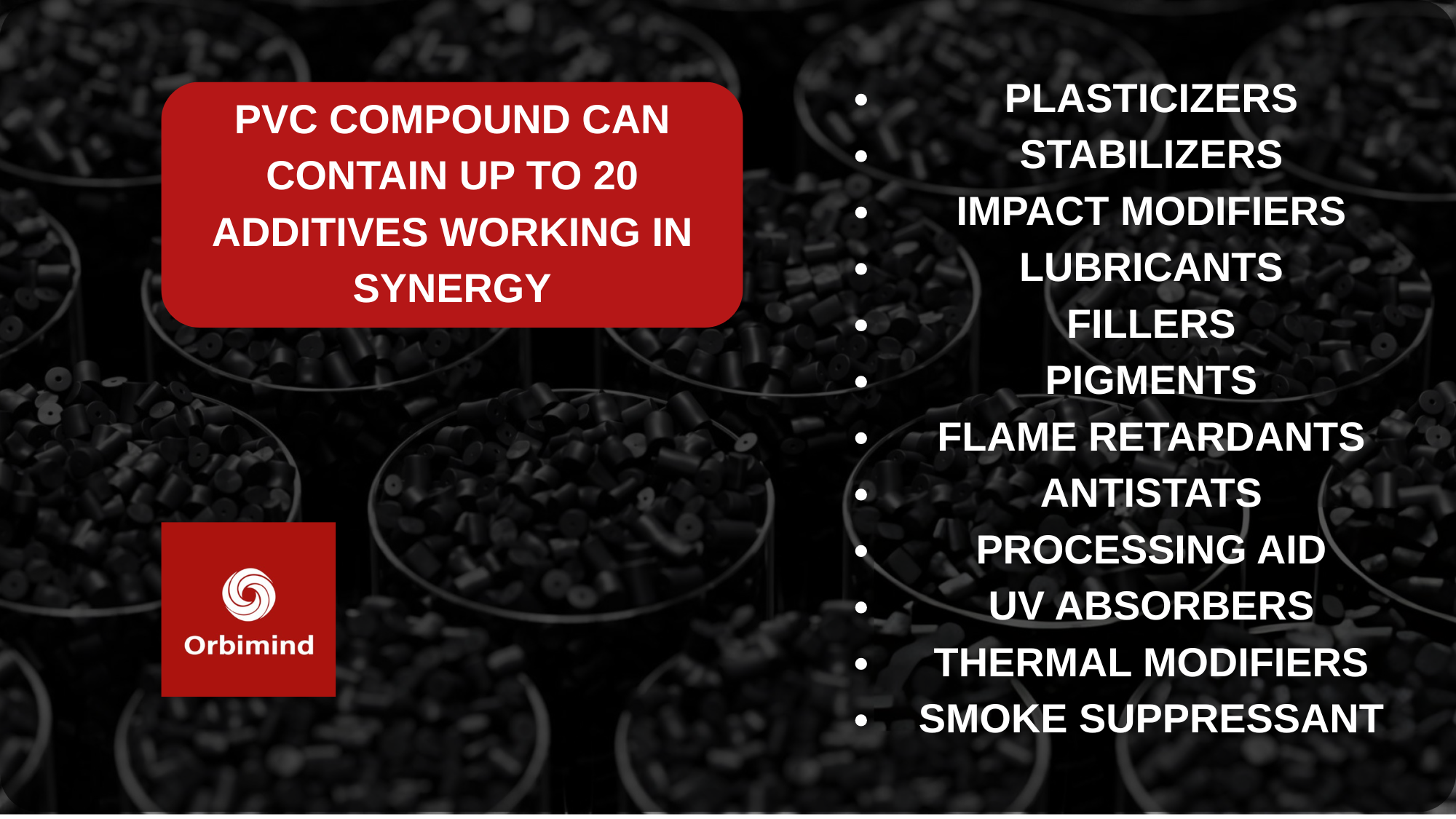

Why Processing Conditions Matter: At its core, PVC is a heat-sensitive polymer that relies on stabilizers to prevent degradation (discoloration and HCl release) during processing[3]. However, stabilizers can only protect PVC if they are evenly dispersed and present in the right form when and where degradation threats occur. High-speed mixing isn’t just about blending—it induces frictional heat and shear that fundamentally change the PVC compound’s microstructure[4][5]. When mixer blades spin at high RPM, they generate heat that softens PVC particles (above ~87 °C, PVC’s glass transition) and causes partial “gelation” or micro-fusion[6]. This pre-plasticization allows additives like stabilizers, lubricants, and fillers to coat and embed into the PVC particles[5]. In essence, a well-tuned high-shear mixer can break down stabilizer agglomerates and achieve a uniform distribution of stabilizer on the resin[7][8]. The result is a homogenous dry blend where each PVC grain is protected.

Mixer Speed & Shear Rate: Mixer speed directly influences shear energy and frictional heating. A faster blade tip speed means more intense particle collisions and heat generation[9][10]. If speed is too low (or mixing time too short), the stabilizer may not disperse uniformly – you risk clumps or “fisheyes” of stabilizer in the dry blend[2]. These un-dispersed bits mean some PVC regions have insufficient stabilizer, leading to local hot spots and early degradation (often seen as isolated brown specs or streaks in the product). Conversely, if speed is too high or mixing runs too long, the mix can overheat or over-shear. Excessive shear can mechanically break down PVC chains, causing pre-degradation (known as shear burning), which consumes stabilizer early and can trigger discoloration[11][12]. Overheating in the mixer can also drive off volatile components of stabilizers or co-additives[13], effectively reducing the stabilizer available during extrusion. The key is hitting the sweet spot: enough shear to ensure uniform stabilizer dispersion, but not so much that you degrade the PVC or the stabilizer itself.

🧠 Thermal History and “Cooking” of the Dry Blend:

The peak temperature and thermal profile of the mixing process (often reaching 120–130 °C in a high-speed mixer) are carefully controlled[10]. Thermal history matters because many one-pack stabilizers (e.g. Ca-Zn blends) include components like stearates, waxes, or epoxides that must melt and distribute. If the mix doesn’t get hot enough, these components might not fully melt or might remain on particle surfaces sub-optimally. If the mix gets too hot, you risk degrading sensitive stabilizer ingredients or partially burning the PVC (evidenced by a loss in dry blend whiteness or a slight odor). In fact, dry blend whiteness is sometimes used as an indicator: unusually low whiteness can indicate over-gelled, over-heated mix (too much “cooking”), whereas overly high whiteness indicates under-heated mix (incomplete gelation)[14]. Both extremes can reduce stabilizer effectiveness. Manufacturers often monitor mixer discharge temperature and time-to-temperature closely – if the temperature rises too slowly, it could mean blade wear or overloading, leading to insufficient friction and mixing[15]. If it rises too quickly, it could overshoot the set point and scorch the batch. The bottom line: two batches with the same recipe but mixed under different conditions can have very different stabilizer dispersion and thermal histories, hence different stability performance. As one study notes, even filling level and blade condition can alter the temperature profile and cause abnormal heat stability time in the dry blend[1]. Uniform stabilizer performance thus demands consistent mixing protocols (speed, time, fill level, ingredient addition sequence, cooling) across all production lines.

💬 Common Troubleshooting Scenarios in PVC Stabilization

Real-world processing isn’t perfect. Here are common scenarios where identical stabilizer packages yield different results, and how to diagnose them:

Poor Stabilizer Dispersion

Symptom: Inconsistent or poor thermal stability, often accompanied by specks, fish-eyes, or uneven color in the product. You might see one batch turning yellow or degrading faster than expected, while another (same formula) was fine.

Causes: Often traced to inadequate mixing. Low mixer speeds, short mixing cycles, or improper ingredient sequencing can leave stabilizers unevenly distributed[2]. For example, adding the stabilizer too early at low temperature might cause it to clump with resin instead of coating it. Insufficient shear means stabilizer particles (especially powder one-packs or stearates) don’t break down and disperse[2]. Dead spots in an improperly loaded mixer or worn blades can also lead to pockets of under-mixed material. The result is some PVC regions have little stabilizer protection, causing local decomposition during extrusion or molding[11].

Troubleshoot & Fix: First, confirm the mixing logs: Was the mixer run at the prescribed RPM and for the full cycle time? Did it reach the target temperature? Ensure you’re following the recommended feeding order – e.g., many formulations add PVC resin first, then stabilizer at ~60 °C, to maximize stabilizer contact with PVC when it’s beginning to soften[16][17]. If dispersion is an issue, increase mixer speed or time modestly and observe if dry blend quality improves (test for more uniform color and particle size). Check for any clumps in the dry blend (sieve analysis can detect oversized particles[18][19]). If clumping persists, consider pre-dissolving or pre-masterbatching the stabilizer: i.e. mix stabilizers into a small amount of PVC or plasticizer first, or use a liquid form, to aid distribution. Also verify lubricant levels – too much external lubricant can hinder dispersive mixing by making the mix “slip” (reducing shear)[20]. In such cases, temporarily reducing lubricant or switching part of external lubricant to internal type can improve shear mixing and stabilizer uniformity. Ultimately, a uniformly dispersed stabilizer will ensure each polymer granule is equally protected during processing.

Volatilization and Stabilizer Loss

Symptom: Unexpected loss of thermal stability or excessive fumes during processing. You might notice a stabilizer-rich formulation still shows early HCl emission or plate-out (deposits) in vents/molds.

Causes: Some stabilizer components (especially in modern lead-free packages) are volatile or prone to sublimation at high temperatures. Overly aggressive mixing or processing temperatures can drive off these components. For instance, organic stabilizers or co-stabilizers (like some polyols, β-diketones, or epoxidized oils) can volatilize if the dry-blend gets too hot. In an extrusion context, insufficient venting or very high melt temperatures can allow HCl or volatile stabilizer fragments to build up, then suddenly evolve. Additionally, certain organotin stabilizers (liquid tin mercaptides) can precipitate or vaporize at high temp, leading to condenser deposits or “burnt” residues[21]. Essentially, the stabilizer isn’t staying where it needs to be – it’s either cooked off in mixing or outgassed during extrusion.

Troubleshoot & Fix: Review the thermal profile: Did the mixer overshoot the intended temperature? If a batch was inadvertently mixed to, say, 140 °C instead of 120 °C, that could evaporate part of a stabilizer (a telltale sign is a distinct odor or visible fumes when opening the mixer). Ensure that mixer cooling kicks in promptly at the end of the cycle to stop heating at the set point[22]. In processing, check extruder zone temperatures and vent vacuum if applicable. A strong stabilizer odor or heavy fume at the extruder vent suggests volatility issues – you may need to lower barrel temperatures or increase vacuum on vents. Sometimes the solution is choosing a more temperature-stable stabilizer chemistry. For example, if a Ca-Zn package is giving trouble at high outputs, a different formulation (with polyol co-stabilizers or with hindered phenolic antioxidants) might better survive the higher heat. Also, verify if moisture is present (since water can vaporize and appear as “volatiles”, carrying some additives with it). Use thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) on the dry blend to see if it’s losing weight at processing temps – a significant weight loss could indicate volatile content. Reducing mixer temperature, shortening residence time in the extruder, or using a stabilizer with less volatile content (for example, higher molecular weight components) are effective remedies.

Shear-Induced Polymer Degradation

Symptom: PVC material discolors (yellow/brown) quickly during processing, sometimes even at normal temperatures. Melt viscosity might drop, or the product has lower mechanical strength than expected. You may see char or black streaks in extreme cases, indicating burnt PVC.

Causes: PVC can degrade not only from heat but from mechanical shear energy. High screw speeds, excessive shear in mixing, or too much regrind can mechanically break polymer chains and generate heat. This shear heating can kick off dehydrochlorination (PVC’s auto-catalytic degradation) even if the set temperatures aren’t extremely high. Once degradation starts (even microscopically), HCl is released which can rapidly consume stabilizers. Essentially, over-shear = early stabilizer consumption, leaving the remaining process unprotected[11][12]. Additionally, high shear can create localized hot spots (e.g., in an extruder’s compression zone or in tight clearances of tooling) where PVC degrades. Indications of shear issues include high motor torque readings, erratic melt pressure, or a rise in melt temperature beyond setpoint.

Troubleshoot & Fix: Investigate the equipment settings: Was the extruder running at a much higher RPM or throughput? Was a screw or tool change made that altered shear (for instance, going to a more aggressive screw design)? If torque or motor load is unusually high, that’s a red flag – it may indicate the compound isn’t plasticizing smoothly (possibly due to formulation imbalance or inadequate lubrication)[23]. Sometimes, insufficient stabilizer can also lead to higher viscosity as PVC starts crosslinking (charring) slightly, which then increases shear – a vicious circle. To break the cycle, consider adding a touch more internal lubricant or process aid to ease flow (reducing shear stress)[20]. Lower the screw speed or reduce back pressure if possible to lessen mechanical work on the melt. It’s also wise to check if the stabilizer system includes any known friction reducers – for example, lead stabilizers inherently provided some lubrication, whereas Ca-Zn systems might need more external lubricant to compensate[24]. If using Ca-Zn, ensure the formulation has adequate lubricants and co-stabilizers (like phosphites) to handle high shear conditions[25]. Monitoring Specific Energy Input (SEI) per batch or per kg of compound can be very useful – it quantifies how much energy (heat + shear) the material has absorbed. Consistently high SEI correlates with higher degradation risk. By keeping SEI within a target range (either by mixing adjustments or extrusion parameter tweaks), you prevent shear over-processing.

Moisture or Contaminant Effects

Symptom: Unpredictable stability issues – one batch suddenly has poor stability or gels, especially after raw material changes or humid weather. You might see porosity or foaming in the melt, or hear popping (from moisture) during processing. Stability tests show anomalies not explained by formula or mixing alone.

Causes: Moisture is a quiet destabilizer. PVC resin itself is not very hygroscopic, but fillers like CaCO₃, woodflour, or even poorly stored stabilizer powders can carry moisture. During mixing, moisture can hinder frictional heating (water’s heat capacity can slow the temperature rise[26]), leading to under-heating and poor additive fusion. Then, in the extruder, that moisture turns to steam, potentially creating microvoids and also accelerating PVC degradation by hydrolyzing some stabilizer components. For example, organotin stabilizers can hydrolyze, reducing their effectiveness. Moisture can also react with metallic soaps (Ca/Zn stearates), forming hydrates or even free fatty acids that no longer protect PVC. Besides water, contaminants like leftover acids, iron or copper particles, or incompatible plastics can deactivate stabilizers. (Trace metals like copper are notorious PVC degraders – they catalyze decomposition, overwhelming stabilizers). Recycled PVC or regrind may introduce such contaminants. Even pigments can have an effect: certain pigments or colorants with heavy metal impurities can destabilize PVC, while others (like TiO₂) might consume stabilizer on their surfaces.

Troubleshoot & Fix: Start with a simple moisture test – check the % moisture of your PVC resin, filler, and stabilizer (if it’s a hygroscopic type). If moisture is above spec, dry the raw materials (e.g., dry the filler in an oven or ensure the resin is stored in dry conditions). During mixing, the process should ideally drive off residual moisture – verify that the mixing step is effectively venting steam (a mixer lid vent or slight open lid at low speed can release initial moisture). As one industry guideline notes, hot mixing should “eliminate moisture and low volatile components” to avoid their impact on product quality[27]. If moisture remains an issue, extend the hot mix time slightly or raise the target temperature a bit (within safe limits) to ensure dryness[28]. For contaminants, trace back any recent changes: new batch of resin? New color masterbatch? Try a burn test on suspect raw materials – PVC with certain contaminants might char unusually fast. FTIR analysis of a degraded sample might reveal unusual substances (e.g. carbonyl peaks beyond normal, indicating contamination). The fix is removal or mitigation: use activated PVC stabilizer systems (some stabilizers include absorbers for impurities), or add a chelating agent if metals are an issue. Ensure all equipment (mixers, hoppers, feeders) are clean – a small bit of residual unplasticized PVC from a previous batch can degrade and seed rapid degradation in the next. Using fresh one-pack stabilizers (if the current supply got humid or contaminated in storage) can also solve mysterious stability drops. Ultimately, keeping the system dry and clean will allow stabilizers to function as intended.

Stabilizer Depletion or Deactivation

Symptom: The PVC compound has acceptable initial color and stability, but loses stability sooner than expected under prolonged heating or multiple processing passes. In other words, the stabilizer seems to “give up” early. For instance, extruded profiles might be fine initially but turn yellow faster in oven aging tests than a comparable batch.

Causes: This often points to stabilizer exhaustion or deactivation. One scenario is when the stabilizer package provides good initial stabilization (preventing early color change) but lacks long-term thermal stability reserve. For example, Ca-Zn stabilizers typically need co-stabilizers (like antioxidants or organic co-stabilizers) to boost long-term heat stability[29]. If those co-stabilizers are under-dosed or consumed by reactions, the later stages of processing (or service life) see degradation. Stabilizer can be depleted by having to neutralize an excessive amount of HCl (maybe due to higher shear or initial PVC quality issues). Filler interactions can also effectively reduce available stabilizer: as noted, fillers like natural CaCO₃ can adsorb stabilizer molecules on their surface[30]. If one plant uses a different filler grade or more regrind, the effective stabilizer present in the PVC matrix might be lower, explaining a shorter stability time. Another cause is antagonistic additive interactions – for instance, certain combinations of additives can nullify each other. One example: using a sulfur-containing organotin alongside lead stabilizer residues can cause cross-contamination and reduce effectiveness[25]. Likewise, if two stabilizers are inadvertently mixed (like remnants of a previous stabilizer system in regrind), they might not work optimally together.

Troubleshoot & Fix: Evaluate the stabilizer system’s balance between initial and long-term stabilizers. If you observe “early yellowing” (initial discoloration), it hints at insufficient initial stabilizer; if you see later degradation after some time, it hints at insufficient long-term stabilizer[31]. Adjusting the stabilizer package may be required – e.g., add a co-stabilizer like a β-diketone or phosphite if using Ca-Zn to improve long-term stability[31]. Also, check dosage accuracy: ensure that the correct amount of stabilizer was added (weighing errors or segregation during handling can occur). Analyze any fillers or pigments in the formula: if a new filler lot has higher surface area, it might be tying up stabilizer – one solution is to use surface-treated fillers (stearic acid coated CaCO₃) so they interfere less with additives[32]. If the PVC compound is recycled or reprocessed multiple times, consider that stabilizers from the first pass may be largely spent; additional stabilizer might be needed for reprocessing. Finally, be mindful of processing equipment surfaces: a highly rough or catalytic metal surface (e.g., uncoated brass parts) can degrade stabilizer or catalyze PVC decomposition. Using proper materials (chromium/nickel-plated surfaces for Ca-Zn systems, for example) prevents catalyst-induced stabilizer burnout[33]. By ensuring the stabilizer system is robust (and not neutralized by something unexpected), you can achieve consistent long-term thermal stability performance.

How to Diagnose PVC Stability Issues: Test Methods

When facing stabilizer performance problems, analytical tests can pinpoint what’s going wrong. Here are key diagnostic methods and what they reveal:

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) & Oxidative Induction Time (OIT): DSC can assess the heat stability and oxidative resistance of a PVC compound by measuring exotherms associated with decomposition. The OIT test, often used for polyolefins, can be adapted to PVC to measure how long the material resists oxidation at a set temperature under oxygen. A longer OIT means the stabilizer system is effective; a short or zero OIT indicates the stabilizers (or antioxidants) are insufficient. Standards like ASTM D3895 or ISO 11357-6 cover OIT tests[34]. DSC can also compare the onset of PVC degradation between samples – if one sample shows an exothermic peak (degradation) at a lower temperature, it’s less thermally stable.

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): TGA measures weight loss as the sample is heated. PVC typically shows a two-stage weight loss: first stage from HCl loss (dehydrochlorination) and a second from the breakdown of the remaining conjugated polyene backbone. By running TGA on samples processed under different conditions, you can see if one has an earlier weight-loss onset. A stabilizer’s effectiveness often appears as a delay in the onset temperature of weight loss[35]. If the TGA curve of one batch drops sooner, it had lower thermal stability (possibly due to less or spent stabilizer). TGA can also quantify volatile content by measuring the initial weight loss at lower temperatures (e.g., water or volatilized additives content[36]).

- Oven Aging / Static Heat Stability Tests: A classic quality test for PVC is to heat samples in a forced-air oven and observe the time to discoloration. ASTM D2115 is a standard practice for oven heat stability, where samples (usually PVC sheets or plaques) are heated at a set temperature and checked periodically for color change[37]. Another widely used method is the Congo Red test (ISO 182 / ASTM D4202) – a static thermal stability test where a sample is heated in a tube and the time until acidic HCl fumes cause a color change in Congo red paper is measured[38][39]. These tests directly measure how long the stabilizer can guard the PVC before decomposition starts. If two supposedly identical formulations give different times (e.g., one turns brown in 20 minutes vs. another in 30 minutes at the same temperature), it confirms a real stability difference[40][41]. This could be due to mixing differences or stabilizer issues as discussed. Such tests are relatively simple and great for spot-checking batches for consistency.

- Colorimetric Yellowness Index (YI): Using a colorimeter or spectrophotometer, you can quantify the color of PVC samples (either initial or after aging). The Yellowness Index (ASTM E313 or D1925) is a number indicating degree of yellowing. A higher YI means more degradation (since PVC forms conjugated double bonds that impart yellow/brown color as it degrades). By measuring YI after a standard heat exposure (e.g., 180 °C for 30 minutes), engineers can compare stabilizer performance. If one process yields a product with a higher initial YI or faster YI increase on aging, it’s less stable. This metric is more objective than visual observation.

- FTIR Analysis (Carbonyl Index): Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy can detect chemical changes in PVC upon degradation. While PVC’s primary degradation pathway is dehydrochlorination (forming polyenes), in the presence of oxygen it can form carbonyl-containing byproducts. The carbonyl index is the ratio of the absorbance of carbonyl peaks (around 1700 cm⁻¹) to a reference peak. An increasing carbonyl index in aged samples indicates oxidative degradation. If one sample shows a significantly higher carbonyl index after aging, it suggests its stabilizer system allowed more oxidation. FTIR can also detect stabilizer consumption – for instance, disappearance of certain stabilizer-related peaks or the appearance of zinc chloride (ZnCl₂) by its fingerprint, which is a byproduct when Zn stabilizers consume HCl.

- Mechanical Property Retention: Ultimately, stabilizers are there to preserve PVC’s usable properties. Testing mechanical properties (tensile strength, elongation, impact strength) before and after heat aging gives a practical measure of stability. For example, you might heat age samples at 100 °C for 7 days (or some standard duration) and then test tensile strength. A well-stabilized PVC will retain a higher percentage of its original strength compared to a poorly stabilized one. Significant drops in mechanical performance upon aging point to stabilizer failure. Standards like ASTM D3045 (heat aging of plastics) can guide such procedures[42]. Also, comparing dynamic thermal stability via torque rheometer is valuable: as mentioned earlier, a torque rheometer can simulate PVC processing and record the time to degradation (often seen as a sudden drop in torque after a period of stable melt processing). This dynamic stability test reflects both heat and shear stability and often correlates with real extrusion behavior[38][41]. If, say, Batch A maintains stable torque for 8 minutes before degrading, and Batch B lasts 12 minutes, Batch B has the more robust stabilizer dispersion[43]. Such tests help troubleshoot whether a problem is formulation-inherent or process-induced.

Troubleshooting Checklist for PVC Stabilizer Performance Issues

When identical stabilizer packages yield non-identical results, a systematic approach can save the day. Use this checklist (and the flowchart below) to diagnose and fix issues on the shop floor:

- Verify Formulation and Ingredients: Double-check that the stabilizer package and dosage are exactly as intended – mistakes in weighing or a mix-up of stabilizer grades can happen. Ensure the stabilizer (and other additives) are within their shelf life and properly stored (no caking or moisture uptake). If a new lot of stabilizer was used, confirm it meets the same spec as before. Also verify the PVC resin grade – different K-values or impurity levels can alter stability, so the resin itself should be consistent. If using a one-pack stabilizer, gently premix or sieve it to break any agglomerates before use.

- Check Raw Material Conditions: Moisture content is critical – test PVC resin, fillers, and additives for moisture. Dry them if necessary. Inspect all additives for purity: any contaminant or impurity (like dirt, metal flakes, or incompatible regrind) can introduce instability. Ensure pigments or fillers known to affect stability (e.g. cadmium pigments or certain clays) are accounted for with appropriate stabilizer adjustments. If processing regrind or recycled PVC, consider that its stabilizer may be partly depleted; additional stabilizer might be needed.

- Review Mixing Parameters: Gather data from the mixing log (or operator). Was the mixer speed, batch size, and sequence per standard? The sequence of ingredient addition should be followed meticulously (e.g., adding stabilizer at the right temperature stage[16][17]). Compare the mixing temperature curve of the good batch vs. the bad batch, if recorded. A slower temperature rise in the problematic batch could mean insufficient shear (due to under-fill or dull blades)[1]. A faster or overshoot might mean over-shear or an out-of-calibration thermocouple. Check the mixer blades and pot condition – worn blades or sticky residue on walls can significantly affect mixing efficiency[19][44]. Clean out any buildup (which could contaminate new batches) and replace or refurbish damaged blades. Ensure the cooling mixer (if a separate cooling step) is working; if hot blend isn’t cooled quickly, it can continue “cooking” and degrade stabilizers post-mixing.

- Inspect Processing Conditions: Examine the extruder or molding machine settings. Are barrel/die zones at the usual setpoints? An out-of-calibration heater or thermocouple can cause actual temperatures to differ from displayed – leading to decomposition[45]. Confirm proper functioning of temperature controllers (no “runaway” zones). Look at screw speed and back pressure – were there recent increases in output that might inadvertently raise melt temperature or shear? If using multiple equipment (e.g., two extruders in different plants), differences in screw design or venting could account for stability differences. For instance, one extruder might need slightly higher stabilizer if it has a longer residence time. Calibrate instruments (thermometers, pressure transducers) to trust your readings[46]. Small glitches like a failed cooling fan or a blocked vent can tip PVC over the edge, so do a thorough equipment check.

- Observe and Sample During Production: Sometimes the quickest clues come from direct observation. Watch a batch as it mixes – is there excessive smoke or smell at a certain point? Does the dry blend appear the same color and density as usual? During extrusion, keep an eye on the melt – is it smooth or are there gels (indicating degraded PVC bits)? Collect samples of both good and bad batches for lab analysis (DSC, TGA, etc., as described above). Immediate checks like a Congo red test on the dry blend[38] or a simple oven heat test on a pressed plaque can tell if one batch was inherently less stable.

- Implement Corrective Actions: Based on findings, apply the fixes: e.g., dry the materials, tweak the mixer speed or time, adjust lubricant levels, increase stabilizer a touch if it was borderline, or replace suspect additive lots. Make one change at a time if possible and measure the effect (to isolate the true cause). Record these adjustments for future reference. Often a minor process tweak (like a 5% longer mix or 10 °C lower extruder die temp) can resolve the issue without needing formulation changes.

- Follow the Troubleshooting Flowchart: The flowchart below distills the above steps into a quick-reference sequence that engineers can follow on the shop floor. It helps decide whether to focus on mixing, formulation, or processing in troubleshooting a stability problem.

Troubleshooting flowchart for PVC stabilizer issues (from verifying formulation, checking mixer operation, to adjusting processing parameters). This flowchart guides engineers through diagnostics and fixes in a logical order.

- Consult and Iterate: If issues persist, don’t hesitate to reach out to the stabilizer supplier or a technical service specialist. They might perform a comprehensive analysis (including checking for interactions or recommending alternative stabilizer systems). In some cases, switching to an alternative stabilizer chemistry might be the solution – for instance, if Ca-Zn one-pack cannot deliver the process window needed, an organotin or newer hybrid stabilizer might be suggested for that specific application (bearing in mind regulatory or customer constraints). Keep an open mind that the “identical stabilizer” might need tailoring to truly behave identically under different equipment.

By following this checklist, PVC processors can systematically identify why a stabilizer isn’t performing and implement changes to regain consistent thermal stability.

Practical Corrective Actions to Improve Thermal Stability

Solving stabilizer performance issues often requires fine-tuning both formulation and processing. Here are some practical actions to consider:

- Mixer Parameter Tuning: Small adjustments in the mixing stage can have outsized effects. Try increasing or decreasing the tip speed of the blades to see impact on dispersion (many high-speed mixers have multi-speed settings[47]). Optimize the mixing time and cutoff temperature: for example, if you currently discharge at 115 °C and see incomplete fusion, you might increase to 120 °C; if you see slight scorching, reduce to 110 °C or shorten the time at peak. Ensure the batch size (fill level) is as per design – under-filling a mixer can reduce friction and over-filling can cause inadequate lifting of material, both affecting uniformity. Monitoring the mixer’s specific energy input (SEI) per batch (if your mixer has power draw readouts) is a great practice – keep SEI consistent batch-to-batch so each batch gets the same “dose” of shear and heat.

- Pre-Masterbatching Stabilizers: If direct addition isn’t yielding consistency, create a stabilizer masterbatch. This could be a highly loaded PVC compound (or a carrier like ABS for certain systems) that contains the stabilizer package pre-dispersed. By introducing this masterbatch into the mix or extruder, you ensure the stabilizer is already well-distributed. This approach is especially useful for liquid or low-melting stabilizers: they can be absorbed onto a carrier resin or filler, converting them into an easier-to-disperse form. It can also reduce dust and loss for powder stabilizers.

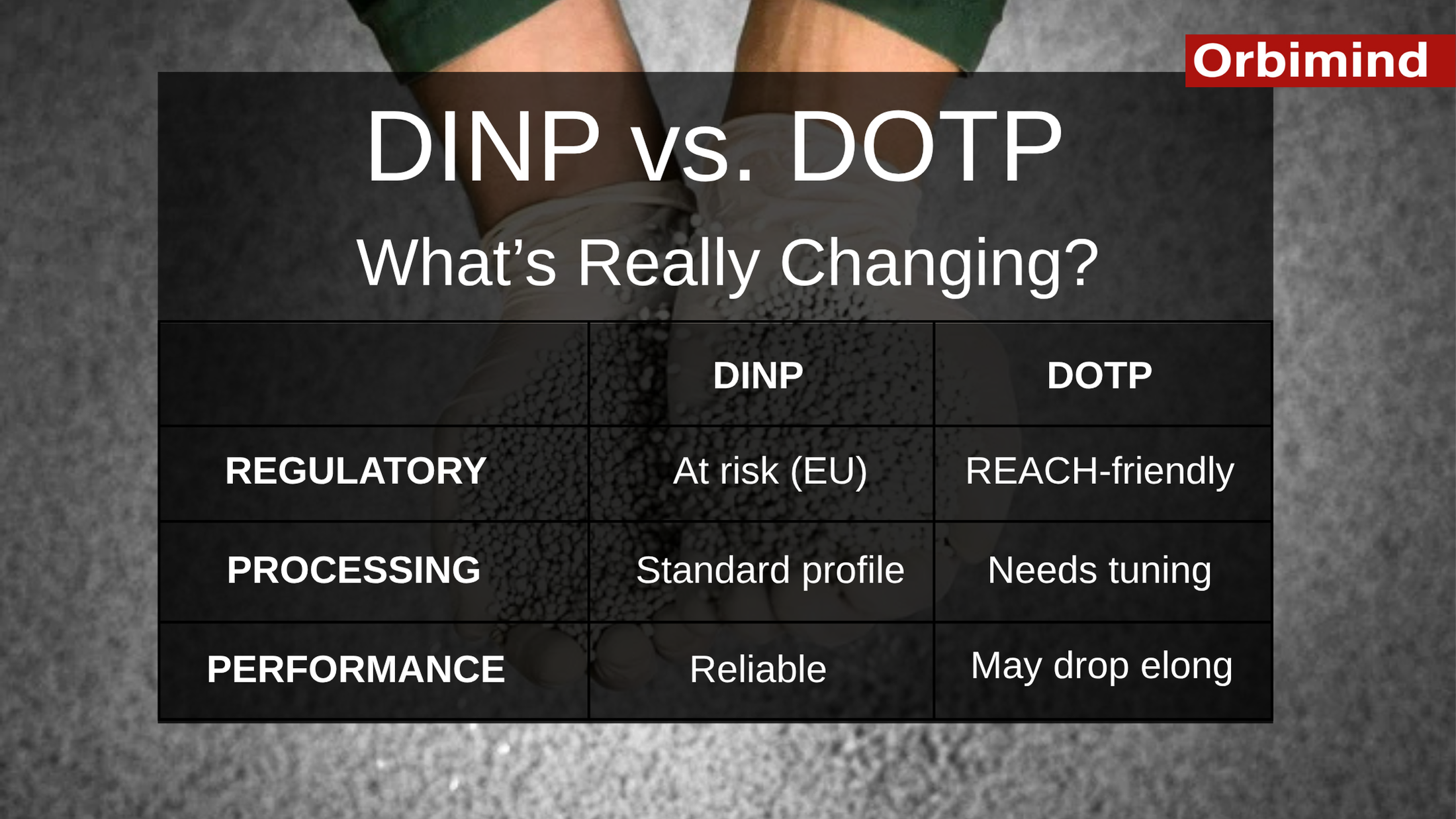

- Alternate Stabilizer Chemistries: Not all stabilizers are equal in every process. If troubleshooting indicates a fundamental limitation of the current stabilizer (e.g., it can’t handle a necessary high processing temperature or ultra-high output rate), evaluate alternatives. Organotin stabilizers, for instance, offer very high efficiency and are less sensitive to processing variations, though they come with toxicity and regulatory considerations. Calcium-zinc stabilizers are environmentally friendlier but often require careful formulation control (lubricants, co-stabilizers) to match tin performance[29][12]. New rare-earth based stabilizers or organic stabilizers (like complex polyols) are emerging, and while they promise improvements, they may demand process tweaks. The key is to align the stabilizer’s strengths with your process needs: high-temperature processes might need stabilizers with higher decomposition points; long residence times might need ones with strong long-term heat absorption capacity. Always test any new stabilizer under your actual conditions (pilot trials) to ensure compatibility.

- Process Monitoring and Control: Introduce or refine monitoring of torque and pressure in your extrusion or molding equipment. A sudden increase in torque can precede a degradation event (as material viscosity spikes due to crosslinking or poor lubrication). Modern extruders can be set to alarm or even pause if torque goes beyond a threshold, potentially saving material from burning. Similarly, monitor melt temperature with in-line sensors – don’t rely solely on barrel set temperatures. A melt probe can reveal if shear is adding more heat than expected. If you see high melt temperatures, you might compensate by lowering heater setpoints or adding cooling. Sequential Energy Input (SEI) monitoring in continuous mixers or twin-screw extruders is also valuable – some systems can measure the cumulative energy put into the material. Keeping that consistent ensures each batch gets a similar thermal history.

- Environmental and Equipment Considerations: Sometimes the fix is outside the formulation: ensure your equipment is appropriate for the stabilizer. For example, if using Ca-Zn stabilizers, make sure the dies and screws are properly plated to avoid metal-catalyzed degradation (zinc chloride from stabilizer can corrode steel and in turn metal chlorides can degrade PVC). Also, maintain a clean processing environment – avoid airborne contaminants (oils, grease, other polymer dust) from getting into your PVC line. If static or dust is an issue during mixing, consider de-dusting or slightly humidifying the environment to avoid contaminant ingress. On the flip side, overly humid environments might require dehumidifiers in storage areas to keep powders dry.

By implementing these corrective actions, engineers can significantly improve the reliability of stabilizer performance across different machines and conditions, ensuring that “identical stabilizer packages” truly deliver identical thermal stability in practice.

Conclusion: Consistency Today for the Future of PVC

In the PVC industry, stable processing = stable profits. The ability to troubleshoot and fine-tune stabilizer performance gives processors a competitive edge. We’ve seen that identical stabilizer packages can behave very differently if mixer speeds or processing conditions diverge – a reminder that processing discipline and know-how are as crucial as formulation. By understanding the science of stabilizer dispersion and using a methodical approach to diagnose issues (leveraging tests like Congo red stability[38] or torque rheometry), engineers can address problems before they escalate into production downtime or product failures. The troubleshooting strategies and best practices outlined here empower teams to achieve consistent PVC thermal stability, batch after batch.

At Orbimind, we believe that sharing such technical insights is key to driving the industry forward. Our annual Future of PVC Conference is a platform where challenges like these are openly discussed and solved collectively. From PVC processing challenges on the plant floor to innovations in stabilizer chemistry, the conference connects engineers, researchers, and decision-makers. By applying rigorous troubleshooting and embracing continuous improvement, PVC manufacturers can confidently navigate today’s challenges and innovate for tomorrow. The future of PVC will be shaped by those who can ensure quality and consistency without compromise – and thermal stability is a cornerstone of that mission. We invite you to join us at the conference, continue the conversation, and be part of shaping the future of PVC. With knowledge and collaboration, we can ensure every PVC product – no matter where or how it’s made – meets the highest standards of stability and performance.

This deep dive was brought to you by Orbimind in anticipation of the Future of PVC Conference. Together, let’s keep PVC processing rock-solid and ready for the future.

[1] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [27] [28] [36] [38] [40] [41] [43] [44] Mixing Process And Mixing Effect Analysis Of PVC Rigid Products – News

https://www.pvcchemical.com/news/mixing-process-and-mixing-effect-analysis-of-p-65607642.html

[2] [12] [20] [21] [23] [24] [25] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] Processing Issues Of PVC Stabilizers – News

https://www.upupstars.com/news/processing-issues-of-pvc-stabilizers-85175736.html

[3] 5 Tips for Processing Heat-Sensitive Resins in Sheet Extrusion

https://www.asaclean.com/blog/5-tips-for-processing-heat-sensitive-resins-in-sheet-extrusion

[9] [10] [22] [26] [47] The Complete Guide to Operating and Maintaining Your PVC High Speed Mixer

https://www.chiyumixer.com/news/pvc-high-speed-mixer-guide.html

[11] [45] [46] Fangli news: Common problems and solutions in the production of PVC pipe production equipment

https://www.fangliextru.com/news-show-855314.html

[34] Oxidative Stability of Polymers: The OIT Test

[35] Kinetics of thermal oxidative degradation of poly (vinyl chloride …

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0956053X20306358

[37] ASTM D2115-04 – Standard Practice for Oven Heat Stability of Poly …

[39] img.antpedia.com

https://img.antpedia.com/standard/files/pdfs_ora/20221211/astm/ASTM%20D4202-92.pdf

[42] ASTM D3045 – Standard Practice for Heat Aging of Plastics Without …

https://www.micomlab.com/micom-testing/astm-d3045/

🔗 Learn More at Future of PVC 2026

If you’re working in formulation, R&D, or technical marketing for PVC-based products, join us at the Future of PVC 2026 conference in Frankfurt, March 11–12.

🧪 Discover:

- Next-gen stabilizer systems

- Data-driven formulation optimization

- Circular additive strategies for recycled PVC